It was an odd week on Planet Earth – the week at the end of November and beginning of December. But a remarkable one too.

I share a booth at Amy’s Antique and Flea Mall. On the last day of November, I was a little over $20 short of my goal for enough sales to cover my part of the booth rental, and I was disappointed. This minor issue seemed to be a judgment on me that felt like criticism. Clearly, I do not stock things that people want to buy. Rationally, I shouldn’t worry about it. The booth is a hobby, not a career. But who wants to feel as if nobody likes your shelves or stools?

This day brought rain storms, which meant surely nobody was going shopping in out-of-the-way antique malls, and I wouldn’t make rent. I had accepted this fate as I was eating lunch with my booth partner Linda Lee. She headed toward the booth afterwards, and I did too. Might as well. Maybe I could move a table or stool into just the right spot to make it irresistible to a passerby.

I was in my car behind hers. When we reached the traffic light to turn toward the building, Linda sailed through. I stopped. I could have pressed on through the yellow, but I braked instead. Then a strange thing happened. When I pulled up to the back where vendors enter, one of the people who works in the booth had fallen while removing items from a truck. When Linda had walked in, the lady was standing. By the time I pulled up after missing the light, she was on the ground and couldn’t get up.

I went to get help, and she is OK now. But I did recognize simple facts. If I had made rent, I wouldn’t have gone to the booth. Also, no one drove by while we were out there assisting her. If I had not missed that light, she would have been out there for a good while longer. It was not hard to draw the conclusion that going for help is a better outcome than improving my bric-a-brac sales.

Cast Bread and Connections

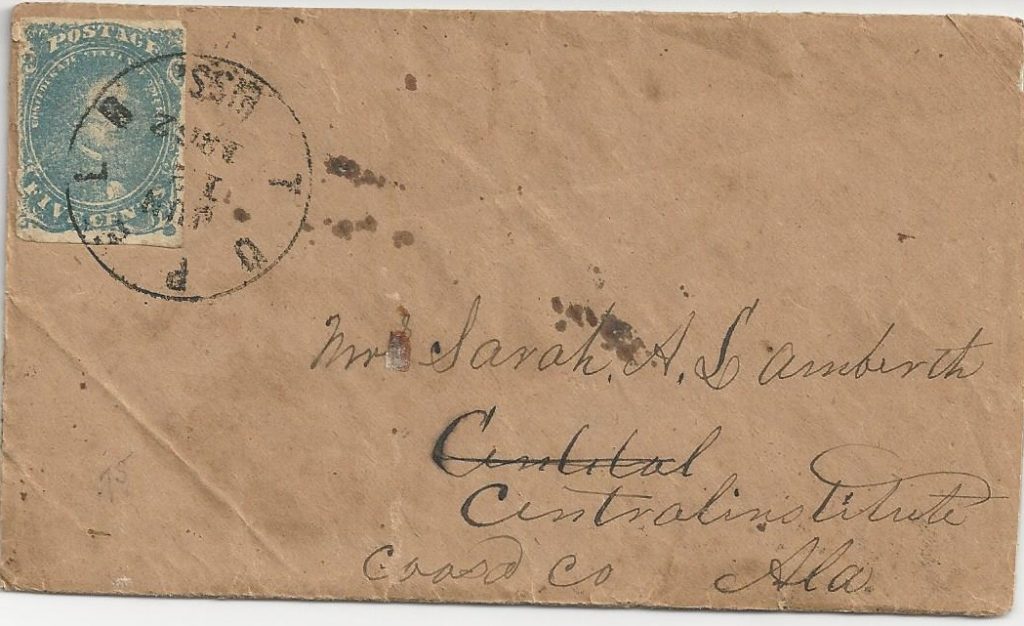

This was a Wednesday, and in this season I was practicing something my mother had once told me: “Cast your bread upon the waters and it comes back buttered.” I had a number of handmade, found-objects art pieces in my house; they weren’t doing anyone any good in here, so I started to send them out through various individuals. Later that afternoon as I headed to my volunteer work in the church kitchen, I grabbed two art pieces to take with me. One of these I gave to my pastor’s wife, Mary Ruth Wolf, when I saw her after the prayer service.

I am a copywriter, as you may know. That is my profession. The next day I had an amazing telephone conversation related to an amazing copywriting project. I am writing several dozen profiles of individuals for a client, and one of these individuals is by nature of his role within the top 10 U.S. military professionals. Gen John Hyten is head of USSTRATCOM based in Nebraska; he reports directly to the Secretary of Defense and to the President. So that’s a high rank. I felt some intimidation as I prepared for the call – which I believed was a reasonable state of being in this case – but I had heard the general was a nice man.

Also, someone on his staff had called earlier to ask me what year I graduated from Huntingdon – an odd way for them to prepare for my questions, but that did mean they checked my website. The caller said he knew someone who went there. In any case, during the interview, Gen Hyten was eloquent on matters great and small, and I was moved by his insights and experiences. As we closed, I prompted, “You knew someone who went to Huntingdon?”

“Yes,” he said, “Linda Crosby.” It took a moment to recognize the name of one of my dearest friends from my class year.

“You knew Linda?” I asked. “I loved her.” As the general explained, he and Linda had grown up together in Huntsville and were good friends. Their families were friends as well.

“Small world,” he said. Indeed.

I met my frequent lunch companion Jan for a quick bite to eat then headed to the McInnis Recycling Center way out on Norman Bridge Road with a trunk full of electronics to drop off. This was the only day of the week they accept this kind of recycling, and sometimes they charge for certain things – like CRT monitors. I had six dollars in cash and not enough time to get to an ATM and across town before the center stopped accepting recycling at 2:00. Maybe my items don’t require payment, I hoped.

The center is staffed by adults with intellectual, mental, and/or physical disabilities. When I arrived, there was a lady who directed me to drive my car into the warehouse to have the electronic items removed from the trunk. Her voice had a different tone – more staccato – compared to the general’s eloquence. But what I noticed was that I did everything she said.

Her instructions were basic: “Drive the car.” The workers took what I had in my trunk, and I was not charged for any of the items being recycled. But as the lady directed me to back out of the warehouse, she asked, “Do you have any money? Read the sign.”

I read the sign. It said, “Donations are appreciated for electronic recycling.” I delayed my departure as I opened my wallet, took out my six dollars, got out of the car, and walked into the office. The worker there asked, “May I help you?”

“I want to make a donation,” I said.

As I drove home, I thought about the authority of the general with the very high rank, and how the lady in the warehouse had her own unmistakable authority. I wasn’t going to disregard her directions for how to proceed and how to give; I complied with her instructions.

My thoughts meandered to the school crossing guard who in her official role is obeyed by people of every station of society. No one drives off and says, “I told that school crossing guard exactly what I thought about her ‘little traffic rules.’” For at that moment, the school crossing guard represents a community’s most tender values: the protection of children.

Then came Friday. That afternoon I had stopped in my booth and felt the familiar disappointment of stocking unpopular, unwanted items. After a heavy sigh, I thought to myself, “I am not going to let this good week end with a feeling of disappointment about a silly booth that represents a tiny fraction of my work life. I’m not going home with this feeling.”

What could I do instead? I said to myself, “I’m going to see Pat Stewart.”

My 85-year-old friend lived in an assisted living facility way out Narrow Lane Road. This was a pretty significant journey for Friday afternoon traffic in December, but I headed down the bypass and found Pat in her room. We had a nice visit. I told her about the phone call with the general, how he knew a friend of mine, and about the timing of my visit to the booth.

We both agreed that you never know what’s happening that you can’t see. I said to her, “I better head back home. It will take a while to get there.” And it did. With accidents amid Friday close-of-business drivers, it took me 45 minutes to get home. I remember not being too bothered by the delay, but trusting that – as I had learned – delays can set up important circumstances. You never know, you know?

Acts with Impact

Then it was Saturday. That morning I felt the familiar disappointment about that booth and my poor instinct for selecting items that anybody actually wants. But there were other things to do that day, and I pushed my inadequate mercantile abilities out of mind. Sometime in the afternoon, while visiting my sister Anne’s house to watch a football game, I checked my email. I had a message from Mary Ruth. It seems that she and Jay, my pastor, had been looking at the piece I gave her that Wednesday, and they were wondering about getting more of them for Christmas gifts… around 25 in total… and would it be possible to have them by Dec. 20.

So I said to my sister, “I’m going home for a moment to count my art pieces. I’ll be back shortly.” There were 14 at home, six in my booth. So, yes, they bought out all my stock, and with these plus a few more, I fulfilled the order.

If anybody else had done that for me, it would have been a very nice thing, and I would have been grateful. But a pastor and his wife have certain roles of influence by virtue of their roles in the church body. The Wolfs’ endorsement of me and my pieces was a large gift to receive, and it meant a lot to me to be the beneficiary of this request of theirs.

I know as well that influence comes within all levels of authority and in all kinds of roles. Life changes in the small acts as well as the big ones.

Many of you may have surmised that that Friday afternoon was the last time I saw Pat Stewart. Some days later, she had a stroke from which she did not recover, and the last few weeks were difficult for her. Then, on Christmas Day, she took her last breath on earth – leaving behind family and many friends, but joining a heavenly celebration with those who had gone on ahead, including a husband, a son and a baby girl who died at birth.

Pat did small things for me that made a big difference. She helped me find a place in Sunday school, for instance. And in her role of delivering juice and crackers to Sunday school rooms, collecting attendance sheets, preparing sweet tea for church suppers and answering the phone at the preschool desk, she touched countless lives over and over – and mine again and again.

So what lesson do I learn from this remarkable week? “There are no ordinary people,” C.S. Lewis wrote in “The Weight of Glory.”

“Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbour is the holiest object presented to your senses. If he is your Christian neighbour he is holy in almost the same way, for in him also Christ vere latitat—the glorifier and the glorified, Glory Himself, is truly hidden.”

Or said another way: Be a good neighbor, y’all.

Listen to that voice… the one that says yes, the one that says no, the one that says wait, the one that says slow, the one that says stop, the one that says go.

Happy New Year,

Minnie